23 April 2021

Publication bias: the problem that won’t go away. That’s the title of a 1993 study by Kay Dickersin, then at the Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, and Yuan-I Min at the Department of Epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins University. In their study, published in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, the two authors define publication bias as “any tendency on the parts of investigators or editors to fail to publish study results on the basis of the direction or strength of the study findings.” More than 25 years later, not only is the problem of publication bias as they defined it still with us, it has metamorphosized into new forms.

Currently, publication bias is recognized as the preference of journals for publishing studies with positive results while rejecting those with negative ones. According to the Catalogue of Bias, a database that defines and lists examples of more than 10 different types of biases in health sciences, publication bias happens “when the likelihood of a study being published is affected by the findings of the study.” In a variant form, publication bias favors publication of papers distorted by spin that impacts their findings or interpretations. Spin might include manipulation of figures, selective reporting of outcomes, among others.

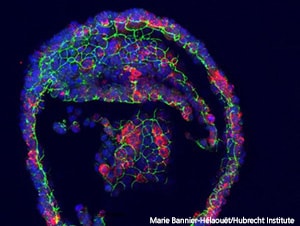

Another type of publication bias occurs when editorial policy and/or peer reviewers of specialized journals request that animal data be provided to validate research findings generated using human biology-based approaches, such as human organs-on-chips and other state of the art technologies. In an opinion piece published in Advanced Science, Dr. Donald Ingber, founding director of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, challenges the idea of considering animal data the gold standard in human health research. Ingber presents evidence that other technologies, such as organs-on-chips, may offer better results and represent a more efficient, ethical and straightforward alternative to animal models.

Dr. Laura Gribaldo knows something about this concern. With a background in microbiology and virology, Dr. Gribaldo has more than 30 years of experience in the fields of testing for chemicals and pharmaceuticals safety assessment. She is a scientific officer at the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission. We were pleased to be able to discuss this topic with her (Dr. Gribaldo’s responses have been edited for length and clarity.).

Interviewer: The topic we would like to talk about focuses on decisions made by the editors of scientific journals and/or peer-reviewers on whether a paper should be accepted for publication based on the type of model applied, be that animal or non-animal models, used to do research that would, supposedly, advance our knowledge about a human condition. In this scenario, publication bias occurs when the decision on accepting a paper for publication does not rely on how effective the model is in mimicking the human condition but rather on maintaining the status-quo that animals should be used as the golden standard for modeling human diseases. What are your thoughts about this type of publication bias?

Dr. Gribaldo: This type of bias is based on a traditional and historical approach that represent sometimes a sort of comfort zone that scientists are not ready to leave. Furthermore, a significant proportion of journals do not have yet any editorial policy relating to the use of animals, and/or they need to revisit and update their editorial policy. As suggested by Hanno Wurbel in a letter published in Nature, if leading journals such as Nature could pioneer such a policy, then it would be in the best interests of editors, scientists and the public, as well as to the benefit of the experimental animals.

Interviewer: Do you have recommendations on how to stop situations characterized by this type of publication bias from happening?

Dr. Gribaldo: As I mentioned above, one way could be to engage high impact journals like Nature and others to develop a dedicated policy to promote non animal models, or at least to start a discussion/forum/workshop with them to understand reasons and concerns.

Interviewer: Many studies and reviews have been published in the last years showing the substantial flaws of using animal models as proxy for human diseases and how low is the translational rate to humans for findings obtained in animals. Nevertheless, a significant part of the scientific community seems to still regard the mouse model as its benchmark. What do you think should be done so scientists will be willing to take the risk of using models other than animals? How should researchers in academia be encouraged to retire the mouse model and adopt models that do not rely on animals?

Dr. Gribaldo: A series of studies produced by JRC’s EURL-ECVAM [Joint Research Centre’s European Union Reference Laboratory for alternatives to animal testing] reviews non-animal models and methods already in use for basic and applied research. The idea for this series is precisely to promote the adoption of these models by the scientific community. The studies consist of an executive summary, a technical report and a knowledge base of collected models. Last year two studies were published, and this year we are going to complete studies in the other five areas of biomedicine selected. We are also promoting an ad hoc campaign of dissemination to reach the target audiences, such as scientific societies, network of universities, animal welfare bodies, and policy makers.

What do you think? Please share your thoughts and comments below.

Post a comment