22 June 2021

by Marcia Triunfol

by Marcia Triunfol

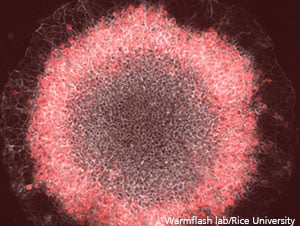

Prof. Dr Hans Clevers is one of the pioneers in the research of adult stem cells and the developer of the first organoids (self-organizing three-dimensional tissue cultures derived from stem cells). A scientist at the University of Utrecht in The Netherlands, Prof. Dr Clevers believes that, for biomedical research, the shift from animal models to adoption of human-relevant approaches is well underway. In his lab only 10% of the experiments currently underway are animal-based and most of the new projects rely on technologies that are not done in vivo but instead use models such as organoids.

A recent study done by Marshall L. et al.(2020) reveals that for research into breast, lung and prostate cancer, the number of publications focused on human organoid models such as patient-derived organoids, which use tumor samples to reproduce individual patient tumor structure and heterogeneity in vitro, has shown a modest increasing trend in the last years. Stronger financial support for this type of study has also been observed, although the total amount invested into patient-derived organoids lags far behind funding dedicated to animal-based xenografts used in research for cancer.

Prof. Dr Clevers recognizes that there is still a long way to go until scientists fully accept the new technologies. One of the reasons for such delay, he believes, is that a substantial fraction of the scientific community has never seen an organoid and still relies on animal data as the gold standard. Prof. Dr Clevers adds that ” a lot of people would argue that organoids are not yet validated to the point that we can abandon the patient-derived xenografts to study cancer”. However, his team members, who have been working with organoids for more than 10 years, share his confidence that organoids reproduce what is seen in organoid xenotransplants in mice. It’s true, he reminds us, that organoids do not have immune systems, but it should be noted that, in the most part, xenografts are done in severely immunocompromised mice.

Besides the many scientific reasons for moving away from using animals, including their failure to replicate the human condition or accurately predict drug responses (with 95% of the drugs effective in animals failing in humans, due to unexplained toxicity or lack of efficacy) and the fact that results cannot be reproduced by other groups, there are ethical reasons and the time-consuming and expensive nature of animal testing to consider. Yet, as Prof. Dr Clevers told us “It seems that every paper submitted to a journal needs to add data on patients, if it is a clinical study, or on mice, if it is more experimental”. He believes that all scientists working with technologies that do not rely on animals know that “among four referees for a paper or grant, around half will ask us to do “real experiments” because they do not know what “these things” (organoids) are.” To have their papers accepted, most scientists will comply with these requests, meaning they will do additional experiments, this time using animals.

This seems to be what happened to a paper published by Prof. Dr Clevers’ group in 2019 in EMBO. An initial, preprint version entitled “Long-term expanding human airway organoids for disease modelling” can be found in the BioRxiv preprint repository. In this version of the study, in which the goal was to “establish long-term culture conditions of human airway epithelial organoids that contain all major cell populations and allow personalized human disease modelling” no animal-based experiments were performed. The group worked with broncho-alveolar resections or lavage material from people with cystic fibrosis and with biopsies from nonsmall-cell lung cancer. In the preprint version, they created lung tumoroid lines by generating p53-mutated cells using CRISPR that took over the wild-type p53 sub-clones from NSCLCs samples. However, in the final version of the paper published in the EMBO journal CRISPR is no longer mentioned, and tumor airway-organoids are transplanted into immunocompromised mice. “This is a popular paper that was very difficult to publish. We had to try three or four different journals, until we had it accepted. I don’t recall exactly at what point we decided to add the animal experiments, but I believe it was done because of a request by an editor or referee from one of these journals” says Prof. Dr Clevers.

Episodes like these define a recently recognized type of publication bias in which editorial policy and/or peer reviewers of specialized journals request that animal data be provided to validate studies produced using human biology-based approaches, such as human organoids. In fact, a survey is now available that aims to better understand the circumstances under which animal-derived data is requested to be added to a study otherwise performed without the use of animals as a condition for publication.

“Phasing-out animal experiments will happen when people are convinced that we have better models and that they are ethically preferable. But I think there are always things we will do in animals” states Prof. Dr Clevers, taking account of current norms.

However, science keeps evolving and what just recently seemed to be impossible, like replacing animals for the study of embryonic development, has started to change with the new advent of gastroloids, which are 3D-cell structures that display the three layers of cells generating all organs in the body and which can be useful to study cell fate and genetic and congenital defects. We cannot predict the future with perfect certainty, but with respect to non-animal technologies we can and should do our best to shape it.

“Paradigms gain their status because they are more successful than their competitors in solving a few problems that the group of practitioners has come to recognize as acute. To be more successful is not, however, to be either completely successful with a single problem or notably successful with any large number.” reminds us the American philosopher of science Thomas S. Kuhn in his classic book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

___________________________________________________________________________

This blog is part of a series on Publication Bias. You may also want to check An interview with Laura Gribaldo on Publication Bias in Biomedical Research and Challenging journal publication bias and redefining the “gold standard” in human health research

What do you think? Please share your thoughts and comments below.

Post a comment